The future is another world

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”

— Arthur C Clarke’s Third Law

As a new decade is about to begin I am drawn to thinking about the rate at which the world is changing and our ability to keep up with that change.

At the start of 1950 I was approaching my second birthday. My memories of that time are almost non-existent – just a few fleeting images lacking any context. My brain was still too busy coping with the basic mechanisms of being a sentient, living being to have much room for organizing incoming information. A framework takes time to construct and without it there’s nowhere to place new facts, so everything goes into a disorganized heap. Perhaps some of it is still there but it’s hard to access on demand.

Notwithstanding my inability to remember those days, however, the world of the time was very real but a remarkably different place to the one we live in now. The Second World War had finished only 5 years earlier, the UK monarchy was headed by King George VI and although the word “supermarket” had been coined a couple of decades earlier the first self-service stores in the UK had only arrived 2 years before. Here’s an arbitrary list of other things that have changed out of all recognition over 70 years:

- The first passenger jet aircraft (the De Havilland Comet) did not arrive for another 2 years.

- The Ford Anglia (below) was typical of the models available for the majority of UK car buyers.

- There was a single 405-line TV channel, available only in the South of England and only in black and white. If you wanted to see programmes in color you went to the movies.

- Radio was AM (Amplitude Modulation) on medium and long wave. FM (Frequency Modulation) broadcasting did not start until 1955.

- The 33 rpm (long play) record had been invented a couple of years earlier but there were no portable music players.

- In the kitchen, a Kenwood Chef cost the modern equivalent of £500. Fridges and washing machines were also luxury goods few could afford.

- Telephones were mostly black, had a dial instead of a keyboard and were connected to the exchange by a cable. Answering machines came later.

Imagine yourself unexpectedly transported back in time to 1950 with just the clothes you stand in. As you encounter this unfamiliar world you discover in your pocket just one attribute of the year 2020; your smartphone. Unfortunately, without a digital wireless telephone network most of its functions are non-operational. In the limited time before the battery expires, how would you establish your credentials as being from the world of 70 years hence by explaining to people what this curious object is and what it can do?

I’ll assume your audience is intelligent and fully up-to-speed with current developments. For example, they would know that the transistor had been invented 2 years ago but would have no idea of its potential.

To start with, the materials used in the construction of the strange device you are holding will be unfamiliar. Although some plastics such as polyethylene had been invented there was no way they could pass off as metals in the way they do now. Sometimes the only clue is by touching; metals feel colder to the touch than do plastics.

When you power up your smartphone in front of your 1950 audience, the shock of seeing a blank slab of glass suddenly reveal pictures in living color will be considerable. The common assumption would be that it was some kind of magic trick involving a hidden cinema projector. So how do you explain to your new friends what is actually going on?

From valve to chip

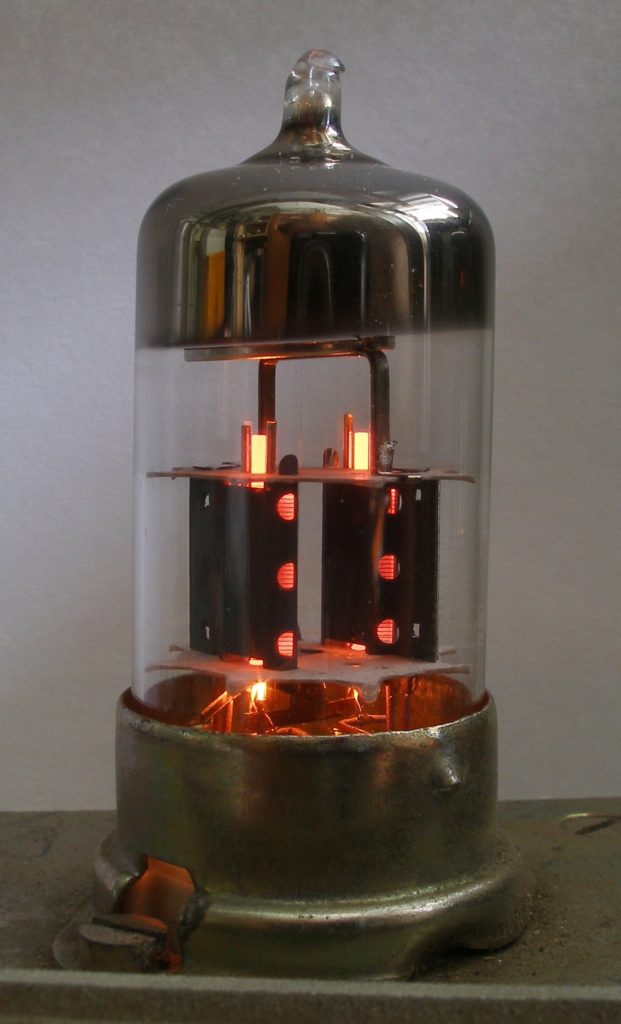

The explanation starts in that time itself, in those early days of the transistor. Before then, wireless radio and TV sets used “triode valves”; glass envelopes similar to light bulbs but designed to perform switching functions rather than generate light. The presence or absence of a voltage on one of the triode pins caused it to pass or block electrical current on two other pins. Two more pins connected to a heating coil, without which the device wouldn’t work. In those days you had to wait for a radio or TV set to “warm up” before it would do anything.

Valves were bulky, they consumed a lot of power and they had a limited lifetime before they “burned out”. The simplest of computers requires hundreds of switching elements so their operators spent much of their time replacing blown valves. The transistor was revolutionary as it did away with the glass envelope. Instead, a blob of one metal on the surface of a small sheet of another allowed the same switching function to take place without the need for a heater. Transistors were smaller, they consumed far less power and they didn’t wear out.

This new invention was revolutionary, permitting all sorts of devices to be built that had hitherto been impractical or impossible. The transistor radio, with just a handful of transistors replacing a similar number of valves, could be made small enough to carry about, and could be run from a battery, thus sparking a revolution in how music could be enjoyed on the move. But there were far bigger revolutions on the way.

Transistors were small and initially they were made just one at a time. The next step was to fabricate more than one on a single piece of the base material, silicon. The race had begun to put more and more transistors onto a single “chip”; first dozens, then hundreds, thousands, millions and so on until we reach the present day where the new Intel Core i9 CPU is believed to contain about 7 billion transistors.

This is too much for your audience in 1950. Seven billion transistors in the space of the smallest coin? This is way beyond anything science fiction dare imagine. So you need to explain how such a thing is possible, which takes us to photography, or to be more exact, photolithography.

Lithography, invented in 1796, is a printing technique whereby a design is created in oil on a stone or metal plate, which is then exposed to an acid that etches away the unprotected areas. Ink is applied to the resulting printing plate but only adheres to the un-etched areas so it can then be transferred to a sheet of paper.

An electronic device with millions or even billions of transistors starts as a large-scale design that uses a very sophisticated version of the above to create the same design in miniature on a piece of silicon. The machines that are built to do this work are themselves extremely complex and cost billions of pounds, so they only become economic if a huge number of chips are to be produced at a price low enough for millions to be sold. The designs referred to above are themselves held in computers that could not exist without some previous version of the same chip being available.

In this way the industry builds upon itself, year after year and generation after generation. The process is called “bootstrapping”; a reference to “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps”, which although impossible in the normal world is effectively what is happening in the world of microelectronics. The magical device you are showing to a 1950 audience is not unique; there’s one in nearly every pocket. They are disposable items we casually dispense with as soon as a better model appears. This notion alone is enough to give 1950s people a headache.

So now, having given your 1950 audience time to recover from the thought of machines creating billions of future versions of themselves, let’s show them what a smartphone can do with the power conferred by the chips that drive it.

Telephony

We all use our smartphone in different ways, but at some point most of us use it as a telephone. Unfortunately, there was no mobile phone network in 1950 so your audience only has your word that a simple slab of plastic, metal and glass can perform the miracle that is telephony. After all, where are the microphone, receiver and dial? Not to mention the cable that connects it to a telephone junction box (there were no plug-in sockets in those days).

This leaves you unable to demonstrate the primary function of the device. So what’s left? How about mapping? Surely that will impress them? Well it would but for the fact that the first satellite, Sputnik 1, went up in 1957, the first mobile phone network opened in 1979 and Google was not founded until 1998. You may have a stored map on your phone but no navigation features will work.

In the absence of anything to demonstrate, you might like to describe to your sceptical audience the nature of telephone networks in 2020, though the changes that have taken place over 70 years are just as mind-boggling as any other part of the smartphone. You could start with satellites. Although there were none in orbit at that time, rocket technology was well advanced. It is interesting that the fastest non-rocket powered plane, the Lockheed SR-71, was built only a few years after your visit to 1950 and still holds that record. Your audience will surely be persuadable that objects can soon be launched into orbit around the Earth, and that some of these objects could hold radio transmitters and receivers able to permit communication with the planet below.

Given the size of aerial required at the time to handle regular radio and TV signals it could be a bigger step to convince them that a device small enough to put into a pocket could communicate at any distance, and in the case of GPS from space itself. But assume you overcome that hurdle, then GPS is the next step. This is after all based on triangulation, well known to mariners and other navigators for centuries. It’s only mathematics, after all. What takes more effort to comprehend is our ability to measure the position on its wave at which each signal arrives, when the waves themselves are microscopically short and operating at frequencies which at the time were inconceivable, and from those measurements establish where the user is to an accuracy of a few meters.

Almost as mindboggling is the way hundreds of phone conversations are crammed into a single transmission during their journeys around the telephone network. Everything – voices, data, music and video – are all hurtling along cables on land and under the sea, between radio masts and out into space and back, and errors are so rare as to be essentially nonexistent. Here we have a triumph of mathematics; algorithms that can overcome errors inherent in any communications channel and deliver a perfect copy of the original, even encrypting and de-encrypting along the way if this is required to prevent eavesdropping. The same mathematical principles are also applied to the recording of compact discs, allowing vast quantities of data to be stored reliably on what is a very error-prone medium.

Images and video

In fact, of all the things you can do with your phone, just about the only ones that don’t require a network are some games and the media player. These are pretty impressive in their own right, of course, though a modern computer game will look pretty baffling to people in 1950. The first video game (Pong) was invented in 1958 and bears little resemblance to any game you’d play on a smartphone. Some of our Solitaire games, though, might be understandable once they get past the idea of being able to interact with a screen by touching it.

The first touchscreen was built in around 1965 but the technology didn’t find its way into phones until the IBM Simon in 1992. Now we have pressure sensitivity and multi-touch with up to 20 or even more touchpoints (for those with that many fingers). Touch technology allows the screen to be pinched and zoomed; it also works with handwriting recognition or the ability to type words by swiping through all the letters they contain. The pattern recognition software that drives this is smart enough to recognize not just words that aren’t in the dictionary but also syntax and even style errors, and offer or substitute better alternatives. To anyone used to a 1950s mechanical typewriter this is close to magic.

Finally we have cameras and media players, each the result of long chains of development over the decades. A camera relies on a panel that is sensitive to light, both in intensity and color, and to achieve the resolution demanded by modern photography a huge number of sensors have to be packed into a very small space as a single chip. As described above, photolithography comes to the rescue. Each sensor point is a transistor built in such a way that light falling on it affects its electrical behavior, allowing the signals from millions of similar devices to be translated into an image. The speed with which this can be done allows many hundreds of samples to be taken every second, enough to achieve video at high frame rates.

Images captured in this way take up a lot of space but the eye and brain do not require all the information to be present in order to see a “perfect” image, so a huge amount of research has been done into discovering just how much can be discarded. This combination of psychology, physiology and mathematics have resulted in algorithms such as JPEG (Joint Pictures Expert Group), which can compress images to a small fraction of their original size without causing any perceived loss of quality. The computations require large amounts of processing power so they are only possible in anything close to real time thanks to the huge advances in computer power that have taken place over the same period.

The ability to take pictures and do complex processing are at their most impressive when used in combination by apps like Instagram to play tricks with reality itself; decorating actual photos with effects that rely on the software “understanding” what it’s looking at so it can add outsized sunglasses to a face or outlandish clothing to a human form. This is merely the latest in a chain of developments that started ten or more years ago with cameras that were able to detect their subjects blinking while the photo was being taken and to warn the camera operator.

Back to the future

Well it turns out there was a mysterious fault in your smartphone itself, responsible for projecting you back 70 years. Once the battery died the projection failed and you have been returned to the present, and once recharged your phone will resume working at it always did. For the people you visited in 1950 your disappearance was as sudden as your appearance.

In spite of your efforts to describe 70 years of future technological development, you won’t have changed history in any way; everything you told them was so outlandish that nobody would believe it in the re-telling. You’d have done better by predicting the first organ transplant, the start of the Korean War or the death of the King to come in February 6, 1952; that way you’d have made your mark as a true seer.

I am left with one thought; suppose a visitor from 2090 were to appear today and attempt to describe his or her world to us. Would we find it any easier to believe the changes that are to come upon us? Or are we, like those people in 1950, prisoners of our time, unable to believe the existence of something way outside our experience until it is a historical fact?

A very Happy New Year to all.

Featured photo by Emanuela Picone on Unsplash